Anti-government protests in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) escalated and in some cases turned violent over the last two weeks, in the governorates of Sulaymaniyah and Duhok. In Erbil, the third governorate in the KRI, streets in major cities were packed with security forces wearing both military and civilian clothes, prepared to suppress any demonstrations; those who tried to protest were immediately arrested.

Throughout the KRI, more than 1.25 million people employed by the Kurdistan Regional Government have been paid nothing since October and earlier in 2020 received only four partial monthly salary payments. The failure to pay government workers is the most blatant symptom of years of fiscal mismanagement and corruption by the ruling political parties in the KRI and Baghdad. The economic crisis has been severely exacerbated by COVID-19 and plummeting oil sales, the mainstay of Iraq’s economy. Iraq continues to borrow money to address the crisis, but it may be paving the way for years of recession and austerity.

As people grew desperate, demonstrations radiated out for the larger cities of Sulaymaniyah and Duhok into the small surrounding cities and towns of the KRI. In some places, protesters burned and looted government offices and party headquarters. In response, government authorities shut down the Internet, blocked all movement in and out of Sulaymaniyah, and detained scores of journalists and protesters, adding to the numbers of activists and journalists who have been in prison for months, many of whose whereabouts remain unknown. Supporters of the protests in the KRI have just launched a new, multi-lingual website that aims to get news of developments out to a larger public outside of Iraq.

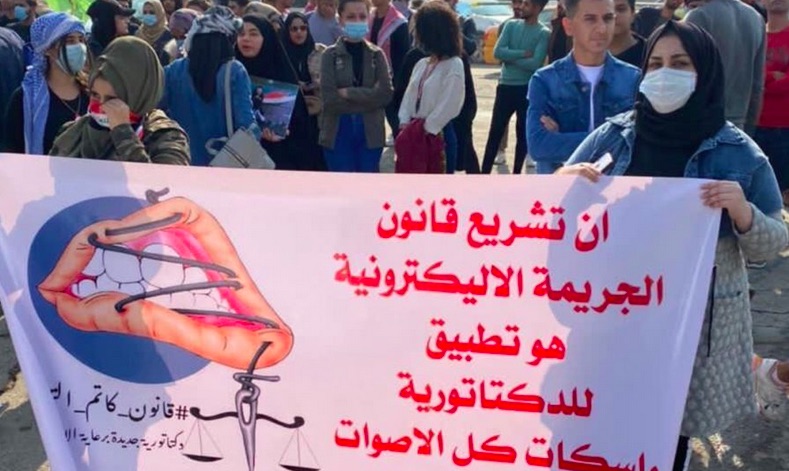

In a potentially devastating further assault on freedom of expression and the right to peaceful protest, the Iraqi parliament in Baghdad is attempting to pass a “Law of Information Technology Crimes” that Iraqi human rights defenders have labeled the “Law to Silence Expression.” The legislation has been severely criticized by Human Rights Watch for being vague and allowing authorities to harshly punish any actions they decide constitute a threat to government, social or religious interests.

Meanwhile in the south of Iraq, especially in the cities of Baghdad and Nasiriyah, anti-government protesters who have been in the streets since October of 2019 are now clashing with supporters of the Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr. At least eight people were killed and dozens were injured in the fighting. Jassim Al-Halfi, a leading member of the Iraqi Communist Party, criticized the killings that followed the storming of al-Haboubi square in Nasiriya, “No to blood dialogue! No to all human killing!” he pleaded. “Who will be the firewood of this violence? No one but the common people, or youth mired in unemployment, and poor people!”

Muqtada al-Sadr, who initially supported the anti-government demonstrations and urged government reform, has recently been positioning himself to run for parliament with hopes of becoming the next prime minister. The idea is completely antithetical to everything the October Revolution stood for: an independent, civil and non-sectarian state free from ties to the U.S. government or to the clerical state in Iran.

A new election law, recently enacted by the Iraqi parliament, changed the basis for voting from a national poll by political party to tallying results for individuals within smaller, local constituencies. This could favor al-Sadr in an election, since he has numerous followers throughout southern Iraq and could win many local elections where other candidates would likely be known in only one or two districts. Elections have been scheduled for early June of 2021, although there is considerable doubt about arranging all the logistics on schedule and delays are expected.

Further unsettling Iraq is another looming human rights crisis caused by government closures of the camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs) who fled their towns and cities when Daesh (or ISIS) invaded in 2014. The overwhelming majority of these people have no homes to return to; many are stigmatized as having perceived ties to Daesh, and they are hindered in accessing the civil documentation essential for employment, education, access to state benefits and free movement. Amnesty International has documented thousands of families across Iraq do not know the fate or whereabouts of their loved ones and who now face an uncertain future themselves.